Natasha Krenbol

Born in Zurich in 1957, Natasha Krenbol grew up between Switzerland and France. Her passion for classical dance, Arabic calligraphy, cartography, graffiti and intuitive painting shaped both her rigour and her free spirit. A graduate of the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1978–82), she pursued her artistic career around the world: Morocco, the Sahara, Canada, California, notably at the Kala Institute in Berkeley.

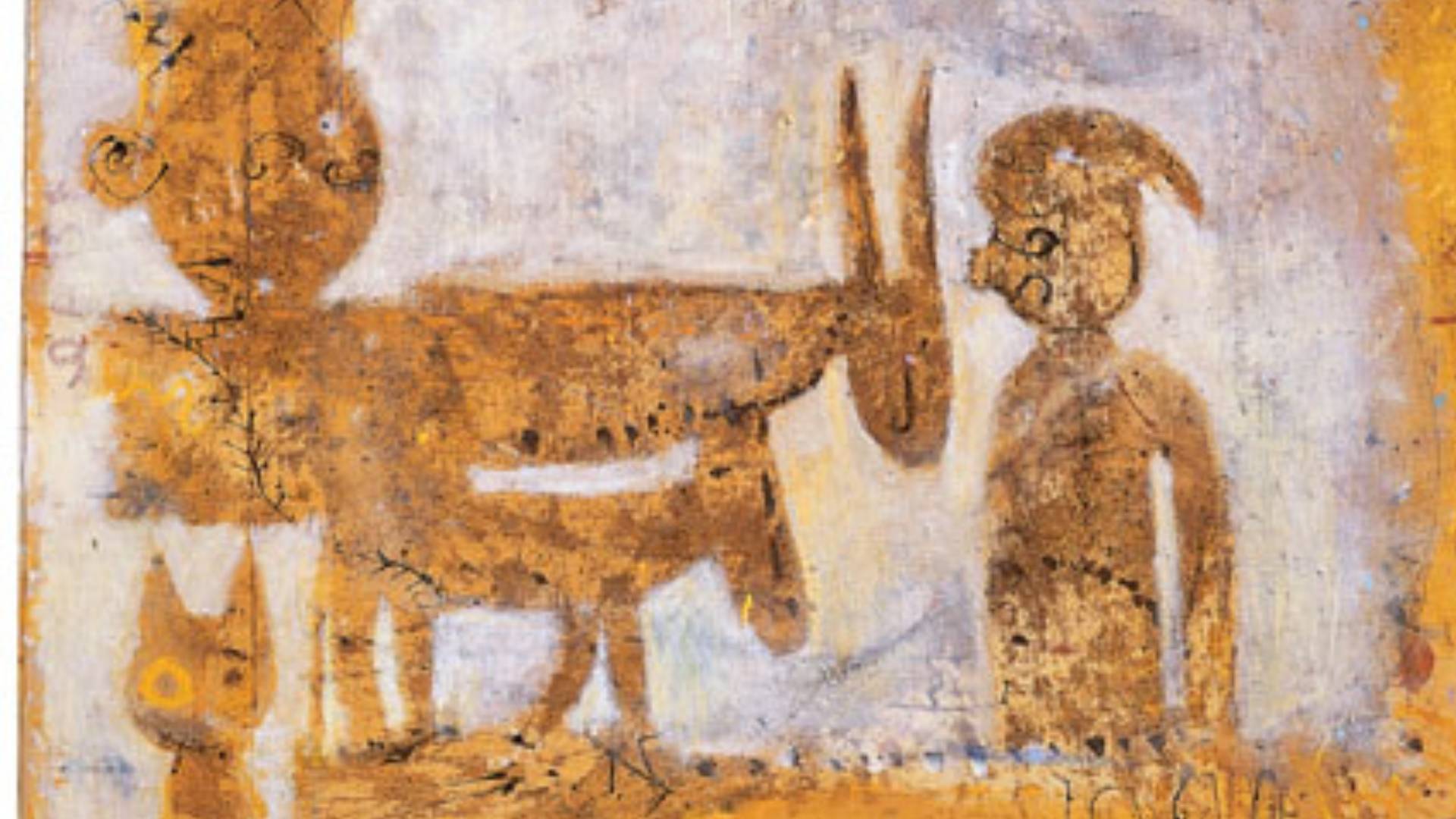

Her painting is the result of the ‘let it come’ method, an intuitive and spontaneous process: the canvas evolves layer by layer, created in chaos, revealing characters, signs, animals and faces. Influenced by Paul Klee, Henri Michaux, primitive art and art brut,

her work cultivates the alchemy between the visible and the invisible, between the sensible and the unconscious.

Why do animals matter?

When asked why animals occupy such a central place in our lives, Natasha begins with a Mauritian sirandane:

Ki lalang ki zame ti manti? Lalang zanimo.

‘What language has never lied? The language of animals.’

With this phrase, she highlights the authenticity of animals, their instinctive truth. They hide nothing, simply reflecting who they are.

Respect, consistency, anti-speciesism

Natasha is very clear: ‘I don’t love animals, I respect them,’ she says. And if she doesn’t eat them, it’s because she is consistent with the compassion she feels for all sentient beings, human or animal.

She describes herself as anti-speciesist: there is no justification for discriminating against a being based on its species.

This fight is social, political and ethical—just like the fight against racism or sexism—because it questions our habit of placing humans at the centre of a hierarchical world. She quotes Gilles Deleuze: ‘Every human being who suffers is an animal, every animal that suffers is a human being.’

Here, Deleuze embodies the awareness of universal suffering: does the animal suffer? It is the human being who suffers, and vice versa.

Egyptian tradition and indigenous philosophy

Natasha also draws inspiration from:

- Egyptian cosmogony, where the kingdoms (mineral, plant, animal, human) are shaped without hierarchy. Humans are not at the top.

- Indigenous peoples, who share this vision of a world of sacred interdependence, far removed from monotheistic traditions that place humans at the centre.

She recalls Montaigne: ‘There is no beast in the world to be feared by man as much as man himself.’ A timeless message about human cruelty, often worse than that of animals.

Painting as a dialogue with animals

In her art, Natasha considers herself ‘like an animal watching animals,’ with the innocence and wonder of a child. She paints ‘signs of animal presence’ (donkeys, fish, cats, etc.) and dialogues with them on canvas as she would in real life.

Her work is a bridge between worlds: it invites us to look at animals differently—neither as simple motifs nor practitioners of folklore, but as ethereal actors in a cosmological narrative.

Ethics & law: Article L214 of the Rural Code

Natasha anchors her convictions in concrete terms, citing Article L214 of the Rural Code:

‘All animals, being sentient beings, must be placed by their owners in conditions compatible with the biological requirements of their species.’

She denounces industrial farming as a curse, but also the extraction of animal sentience, reduced to a mere ‘mineral’ devoid of emotion, consciousness, and intelligence.

She highlights the unprecedented violence of slaughterhouses, not only for animals, but also for the humans who work there: how can they bear such barbarity?

L214: testimony & activism

Natasha talks about L214, a French animal rights organisation founded in 2008, known for its hard-hitting investigative reports exposing the living and slaughtering conditions in intensive farming.

The association is based on a fundamental principle: recognising animal suffering and

taking action to reduce or abolish it.

What this teaches us

Through her response, Natasha invites us to reflect on four key points:

- Animality as truth: animals express themselves without deception, embodying raw and natural emotions.

- Ethical consistency: if we feel compassion for humans, why not for animals?

- Deconstructing hierarchies: spiritual and philosophical tradition invites us to rethink our place.

- Political action: laws, activism and documentation transform emotion into responsible citizenship.

By combining artistic creation and activism, Natasha reminds us that looking at an animal also means connecting with others, with humans, and with all living things. And that in terms of respect, laws and practices, we have responsibilities: to reject hierarchy, to listen to sensitivity, to act for justice. Animals, in all their presence, are essential, beautiful, necessary – and worthy of our commitment.

Recommended resources

- L214, A voice for animals de Jean-Baptiste Del Amo (Ed. Arthaud, 2017) : a powerful testimony to citizen action in favour of the animal cause.

- L’association L214

- Works & career of Natasha Krenbol